The underrated applicative functor

Developers who enter the realm of functional programming quite quickly stumble upon the dreaded “M” word - “monad”. It usually takes a while to comprehend it, the path often involves learning concepts of functor and applicative. Once monads are mastered, applicative functors may appear as intermediary abstractions which are not really interesting. During last Scalar conference in Warsaw, Jan Pustelnik gave a talk "Cool Toolz in Scalaz and Cats Toolboxes” where he presented various handy functional patterns and constructs, mentioning a few interesting advantages of applicative functors. Jan’s statement that he often prefers them over monads made me explore this topic further. Here’s a collection of the most important features and arguments for choosing applicatives (thanks Jan for clarifying this to me!). I will use examples based on the Cats library.

What are applicative functors?

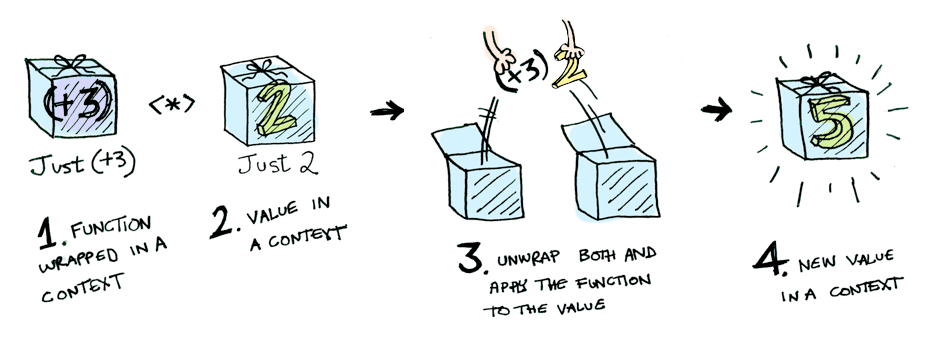

First of all, applicative functor forms a typeclass which can be implemented in Scala. It allows applying a wrapped function to a wrapped value. Here's a depiction from “Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures”.

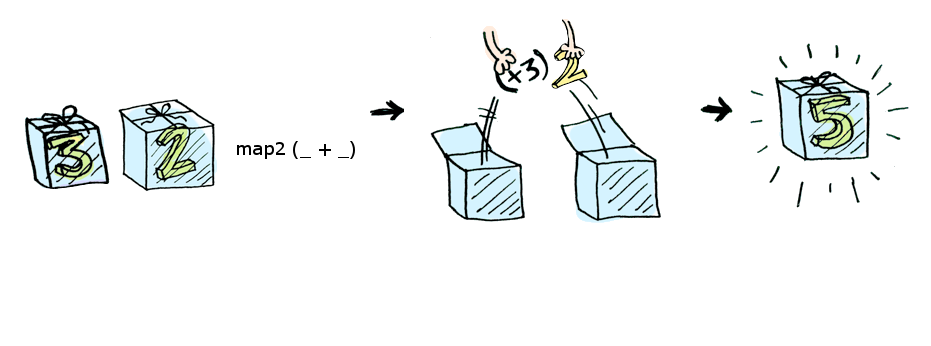

However, I think that it would be better to start with a bit different approach. We can think of applicative as a type which wraps a value. Having two such wrapped values, we can apply a two-argument function to these values and preserve the outer context (wrapping). If we call this “application” map2, then we can get something like this:

This way of looking should bring us a bit closer to more practical understanding. Having two wrapped values is much more familiar than having a "function wrapped in context”.

Independent calculations

Monads impose certain structure to the flow. We apply a function to the wrapped value and we receive a new wrapped value which becomes "flattened" with the outer wrapper. This means that getting subsequent wrapped values depends on results of previous calculations. A typical example would be something like:

for {

user <- getUserFuture()

photo <- getProfilePhoto(user)

}

yield Result(user, photo)The getProfilePhoto() function depends on user, so calling Future[Photo] is possible only after we fully resolve the previous step, Future[User]. However, we often find cases like this:

val res: Future[Result] = for {

user <- getUserFuture()

data <- getDataFuture()

}

yield Result(user, data)In this example, we deal with independent Future[User] and Future[Data] which we want to uwrap and pass to Result.apply. Why would we need monadic flow, which forces us to view this code as a sequence of steps? Here’s a good case for applicatives. All monads are also applicatives, we can just work with Future, Option and many other well known types. There are even more applicatives than monads, in fact. When we decompose our example, we get:

import cats._

import cats.instances.future._

val wrappedFunction =

getDataFuture().map(data => { (user: User) => Result.apply(user, data)})

Applicative[Future].ap(wrappedFunction)(getUserFuture())Now what is THAT?! you may ask. Bear with me, this is an intermediate step. I’m showing this example only to present the apply operation (known as <*> in Haskell). The ap() function allows us to get a wrapped function and fuse it with a wrapped value, just like on the first image.

Cartesian builder

In order to look at applicatives as a way to call a function on two wrapped values, we can use a tool called cartesian builder. It allows expressing our intent as orthogonal composition:

import cats.instances.future._

import cats.syntax.cartesian._

(getUserFuture() |@| getDataFuture()).map(Result.apply)The “scream” operator |@| (also known as “Admiral Ackbar” or "Macaulay Culkin”) finally gets us what we wanted - our independent computations are now represented in a much elegant way. The monadic flow may look like imperative code, while here we have a more functional representation of our actual intent. Apart from adjusting code structure we help future readers to recognise parts that can be parallelized or refactored due to their independence.

Another good example is the Validated applicative, again available in Cats toolbox. Its dual in Scalaz, the Validation applicative was often called “a gateway drug to Scalaz”. Validated allows performing a series of validations but it doesn’t stop the chain in case of failure. All failed validations are accumulated into one final result, which carries full, combined error. In following example:

val result = (validateName(name) |@| validateAge(age) |@| validateEmail(email))(User.apply)our result value can be of type Validated[NonEmptyList[String], User] which we can extract to get all separate error strings. For more details on the Validated applicative, see Eugene’s tutorial.

Traverse / sequence

Applicatives bring another powerful tool, let’s jump straight to the example:

import cats.syntax.traverse._

import cats.instances.list._

import cats.instances.option._

val result = List(1L, 2L, 3L).traverse(getUserByIdOption)

// result = Some(List(user1, user2, user3))The traverse function walks our list using a provided function which returns an applicative. In this case, it’s getUserByIdOption(id: Long): Option[User]. A typical mapping function would return a List[Option[User]] while traverse gives us an Option[List[User]]. This can be achieved by folding the list and rebuilding it with map2 applicative function. There’s also sequence which is just a traverse using the identity function, useful if we already have a list filled with applicatives.

import cats.syntax.traverse._

import cats.instances.list._

import cats.instances.option._

val result = List(Option(1), Option(2), Option(3)).sequence

// result = Some(List(1, 2, 3))

val failed = List(Option(1), None, Option(3)).sequence

// failed = NoneComposition

There’s one more interesting property of applicative functors. When it comes to stack them on each other, the result type is still an applicative. This means that a List[Option[T]] represented as S[T] (where S = List[Option]) can also be used with the |@| builder. Okay, but what does that really mean? Well, if you are familiar with monad transformers, you know how painful they can be. Wrapping monads with another is not enough, because we loose ability to flatMap the most inner wrapped value. Hence we have to either use transformers or tools like Eff / Emm. Applicative functors are free of this burden. You can still use the benefits of fusing together two applicatives with a function, without any extra types. Unfortunately it’s still not easy to express this in Scala.

Free applicatives

Untangling independent calculations with applicatives allows us to build code structures that may be analyzed statically as well as optimized with parallel processing. This becomes much more apparent with free applicatives, which I’ll leave to be covered in detail in another blogpost. For the curious - here’s a great presentation by John de Goes on this subject.

Summary

Applicative functors should be an important tool in our box, just like monads and other fundamental typeclasses. Knowing the best abstraction to represent our intent is a key skill in software engineering. Hopefully understanding their nature and practical qualities will let you improve your functional design and encourage you to explore Cats and Scalaz in depth.