Entry-level, synchronous & transactional event sourcing

Event sourcing is an approach in which changes to application state are persistently stored as a stream of immutable events. This is in contrast to typical CRUD applications, where only the "current" state is stored and mutated when commands come into the system. There's a lot of great introductory material on event sourcing available (see for example Event Store docs, Martin Fowler's article or the CQRS FAQ), so I'll try not to repeat these. The blog is inspired most directly by Greg's Young "Functional Data Storage" talk (you need a Parleys subscription, though).

The best thing about even sourcing is that you don't lose information, and after all, information is what IT is all about (well, you don't lose as much information as in CRUD systems). Events provide a great audit log "for free" (which is something I worked on quite a bit, see Hibernate Envers), but also allow to capture and re-create the application state at any point in time, or provide new views of existing information with ease.

Event Sourcing is quite often described together with Command-Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS), and not without a cause, when using ES some form of CQRS emerges almost naturally. We'll also see "commands" and "read models" later in the blog, however we won't be using CQRS in its most "radical" form.

Event Sourcing is often presented in asynchronous architectures, which take advantage of message queues, multiple databases and where the read model is eventually consistent with the user commands. However, you can of course use Event Sourcing in much simpler setups as well, with a single, relational data store, using transactions to maintain (at least some) consistency. A lot of "business"/back-office applications, which are not distributed and run on a single node, can still gain a lot of benefits from event-sourced architectures. Let's see one possible approach, first described in general, language-agnostic terms and then on a concrete example implementation using Scala+Slick.

General approach

Data model

As our main "source of truth", we'll be storing all events that take place in the system in an events table. Each event is associated with a single aggregate (term borrowed from DDD), and contains some useful meta-data:

- unique event id

- event type: typically the name of the class containing event data

- aggregate type: name of the aggregate's class

- aggregate id

- aggregate new: flag indicating if the event concerns a new or existing aggregate

- created: timestamp at which the event happened

- user id: optional id of the user or other actor which triggered the event

- tx id: groups events triggered in a single transaction

- data: serialized event data, e.g. JSON

For example, let's say we have a very simple application in which users can login, register and generate api-keys to access the app programmatically. A single api-key is created automatically after registration, and a welcome email is sent. I think this scenario should be familiar to most of us.

When a user registers, we have a UserRegistered event (events should be always in past tense), which creates a new User aggregate with a new id. This should be grouped in a single transaction with an ApiKeyCreated event, which is associated with a new ApiKey aggregate.

As we take security seriously, we also store events when users log in. Hence we have a UserLoggedIn event, associated with the already existing User instance.

After the user registers and logs in our events table can look like this:

| id | type | agg | agg id | agg new | created | user id | tx id | data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | UserRegistered | User | 45 | true | 2015-09-09 | 45 | 95 | {"login": "adamw", ...} |

| 101 | ApiKeyCreated | ApiKey | 819 | true | 2015-09-09 | 45 | 95 | {"apikey": "2czw92..."} |

| 102 | UserLoggedIn | User | 45 | false | 2015-09-10 | 45 | 96 | {} |

Note that events don't need to have any data, e.g. in case of UserLoggedIn everything that we want to store is in the meta-data already.

Read model

Events capture all the changes in the system, but querying them directly to read data wouldn't be very convenient. That's why we need read models that should be populated in response to events. As the events are our main source of truth, we can safely de-normalize data here if that's required for serving data efficiently. To create read models, we will define a number of model update functions.

A model update can be seen as a pure function: event => state => state, that is we take the event, the current state of the read model and create an updated read model.

In our example, we will have two trivial read models, one for users and one for api keys. They will be both tables in our relational database, so reading data from such a system should feel very familiar - we can use SQL selects, joins etc. The main difference is that we don't modify the users and apikeys tables directly, but in reaction to events.

Model update functions can also be used to re-create the read model using only the events (by calling model update on subsequent events starting from the first one). Or, if we want to add a new view of the data, we should feed events to the subset of model update functions which create the new view.

Event listeners

We also need a place to run the actual application logic, in reaction to events happening in our system. As a very simple example, how can we send an email after a user has registered? It's not an action that updates the read model, so we can't use model update functions. We also don't want to resend the email when re-creating the state of the database from events. Hence we need a separate category, event listeners.

We'll store both model update functions and event listeners in a registry, which will be used when a new event is triggered in the system.

As we'll see later, event listeners can also trigger new events. As no state is modified here, they can be again seen as a pure function: event => state => list[event], that is we take in the event, the current read model state, and produce a list of new events.

Commands and data validation

How are events triggered and how is data validated? To model these cases it's useful to introduce the concept of commands. A command takes user input, validates it and either returns a validation error or results in a number of events.

Commands can also return values upon success, e.g. the id of the newly created user. Again, it can be seen as a pure function: data => state => (result, list[event]), where data comes from the user and state is the current state of the read model.

For example, when registering a user, as user input we take the username, email and password. We can validate that no user with the given username/email exists using the read model, and either return a validation error or create a new UserRegistered event.

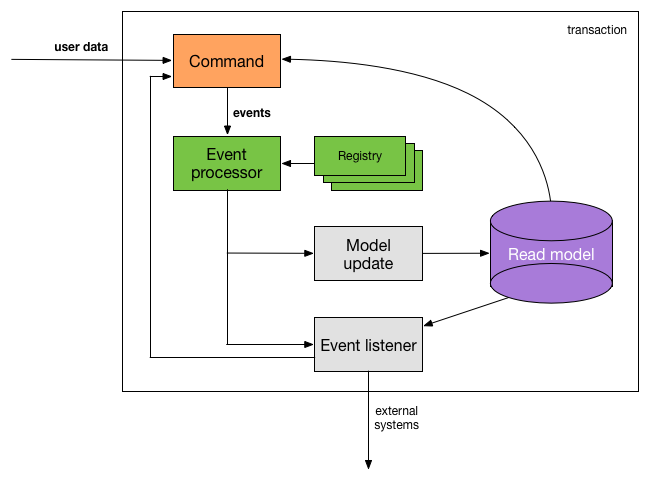

Event processor

Where do all these events go? We need some kind of event processor which, given an event, will first run the model update functions, then the event listeners, then again handle any events that were triggered by the listeners.

The processor also handles commands: takes a command to run, handles all the events and model updates triggered by it, and returns the final result (either a validation error or the result of the command). Moreover, it can do so transactionally, which is a very important feature: the validation that checks username uniqueness is run in the same transaction as the model update after registering a user; updates to the events table and to read models are done in the same transaction, helping to ensure that the two don't get out of sync.

More complex behaviors

So far we've seen relatively simple logic, where one command was triggering one event, which caused a single model update, had a single event listener and that's it. However real life is usually more complex. How, for example, can we create a new api-key after a user is registered?

To create api keys, we have a separate command. The command itself can use the read model, returns a list of triggered events, but most importantly, doesn't modify the database! Hence we can safely call that command from a UserRegistered event listener, and return any events created by the command as a result of the event listener. The event processor will handle the newly produced events, and so on, until no new events are triggered.

The final sequence of registering a user in our example is:

- we pass in a command to register a new user to the event processor (e.g. from an API endpoint)

- event processor: runs the command,

- command: does a lookup in the

userstable by-username and by-email to perform validation. When no existing users are found, it returns a list with a single event,UserRegistered - event processor: we look up model updates in the registry; there's one

- model update: inserts a new row to the

userstable - event processor: we look up event listeners in the registry; there are two: sending e-mail and creating api key

- event listener: sends a welcome email (either synchronously or asynchronously)

- event listener: runs the

create api keycommand obtaining a list with a single event,ApiKeyCreated - event processor: handles the event, updating the model; no further event listeners are found

Component summary

We introduced a number of components, so let's sum up:

- event: stores meta- and regular data about an event which occurred in the system

- read model: created based on events using model update functions (

event => state => state), fulfils the query needs of the application - event listeners: run application logic in response to events, can trigger new events (by running other commands) (

event => state => list[event]) - command: validates user input, triggers events created from input data (

data => state => (result, list[event])) - event processor: handles events, executes commands, runs model updates and event listeners, manages transaction scoping

We can view the whole setup as three pure functions plus the read model and the model update/event listener registry. You don't need any frameworks, special datastores, etc. to do event sourcing! All of these function should be relatively simple and easy to understand.

Scaling

Of course, we can't and shouldn't fit everything into our transactional model. If the application and user base grows, at some point we'll need to introduce other data stores, message queues etc. However nothing stops us from doing just that: we can publish all of the created events to a message bus; we can run some of the model update functions asynchronously, and so on.

You need very little supporting code (as the example below will demonstrate) to do event sourcing, so you are free to modify it so that it suits your current needs.

And with events, you have all of the history stored, so you are safe if you want add a new data analysis module, create a new data view or move to a different data store and re-create the data there.

Scala+Slick example application

The sources for the example application are available on GitHub. The example is extracted from UpdateImpact, so while it's not written from scratch as an example and might be rough around the edges, it's based on a working application.

You can run the example by invoking sbt "~example/re-start". Try registering, logging in & out, you'll see some events logged to the console (and of course data written to the database!).

The project contains two modules: events with the generic code related to event-sourcing, and example with a specific usage example of the event sourcing infrastructure (where a user can register, log in & out, create api keys as described previously).

Events

The central type is Event defined in model.scala, which can be constructed incrementally using a DSL. The data associated with each event is stored in plain-old-case classes; the event type is the name of the case class, and the data is serialized to json. For example, creating a new "user registered" event and marking that it's a new aggregate in the event meta-data looks like this:

val eventData = UserRegistered(login, email, encryptedPassword, salt)

val event = Event(eventData).forNewAggregateNote that this is not yet a fully constructed Event object, some fields like the event id, aggregate id or transaction id are filled automatically later.

The aggregate for an event is determined via an implicit AggregateForEvent[EventType, AggregateType value, for example defined in the companion object for the event data class, thanks to which the implicit will be looked up automatically:

object UserRegistered {

implicit val afe = AggregateForEvent[UserRegistered, User]

}Another feature, which is entirely optional and not required for event sourcing, but makes life much easier, is type-safe aggregate ids. At the database level all ids are Longs, however both in event classes, event data objects and objects read from the database you can see that the Longs are tagged with the type of the aggregate (e.g. case class User(id: Long @@ User, ...). The tagging here is using scala-common.

Side-effects

In the code we make heavy use of Slick's DBIOAction monad, which wraps all side-effecting operations that may involve the database. Thanks to Slick's strict control of access, we know if an action is reading from the database, writing to it or both; for convenience, DBRead and DBWrite type alises are defined.

Using DBIOAction, our code creates a description of the actions that should happen (like: emitting an event, storing the event in the database, updating the read model etc.), the actual execution happens later. You can see that in EventMachine (which is the event processor). All of the actions are gathered, sequenced, then a simple .transactionally call makes sure that they are all run in a single transaction.

In fact, EventMachine also returns a DBIOAction. So when are thing really run? In our case, this happens at the API level: take a look at DatabaseSupport, there you can see Akka HTTP directives which run DBIOActions and return the results to the caller.

Also, any Futures can be lifted to DBIOAction, if the side-effect that we want to run doesn't involve DB operations, but e.g. sending an e-mail.

Commands

Commands are simply methods which return a CommandResult, which is an alias for a database action returning either a failure or success value, plus a list of triggered events. These events should be handled by the event processor and can, in turn, trigger more events. That's what happens in the EventMachine.handle(CommandResult) method.

Take a look for example at UserCommands. In the authenticate command we do some validation (checking the password) and return either a successfull or failed command result. The CommandResult companion object (although CommandResult is only a type alias, it can have a companion object) defines some helper methods for returning results with a list of events.

Model updates, event listeners

Model updates and event listeners are again defined as type aliases for function types:

type EventListener[T] = Event[T] => DBRead[List[PartialEvent[_, _]]]

type ModelUpdate[T] = Event[T] => DBReadWriteAn event listener can read from the database and emit any number of events as a result, and a model update can both read from the database and update it (as it updates the read model).

We can see a couple of listeners for example in UserListeners, updating the last login date for a user looks like this:

val lastLoginUpdate: ModelUpdate[UserLoggedIn] = e => userModel.updateLastLogin(e.aggregateId, e.created)As you can see it's a plain-old-Scala-function!

Bringing it all together

We still need to somehow register the event listeners and model updates, create the objects that contain the commands and so on. For that, we are using the thin cake pattern, which is nothing else than defining a trait with some part of the object graph defined.

For example, here's the UserModule, defining how to create all user-related objects: user commands, user read model and the depedencies of the module.

The event listeners/model update functions are added to the Registry (which is used by the EventMachine to lookup what should be done in reaction to an event), by defining a method which takes an old Registry and returns an updated one. This is used in Beans, where all of the modules are brought together (here there are only two of them).

Handle context

The final piece is the HandleContext class, which must be implicitly available when events are run. This holds the id of the currently logged in user, as well as the transaction id (which is automatically filled). For example in ApikeyRoutes, you can see that a HandleContext is created basing on the session content. This is later used by the directives that run commands (e.g. cmdResult) and passed to the EventMachine.

Summing up

Event sourcing is a great pattern allowing to conveniently store much more information than in a traditional CRUD application; you never know when this data can be useful! You can implement event sourcing while using a single, strongly consistent, transactional database, retaining the familiar SQL model for reading data.

Also - you don't need a framework or even a library to use event sourcing. The Scala/Slick code shown here is just a bunch of classes and type aliases (which make code more self-documenting and easier to understand); you can implement similar micro-frameworks in other languages as well of course.

As always, any comments appreciated! If you have ideas for improvements, either in the general idea or the code - let me know!

Ready to dive deep into Event Sourcing in Java? Subscribe to SoftwareMill Academy and get a series of in-depth tutorials.