Free monads - what? and why?

If you're starting to get into functional programming, or rather diving deeper and deeper, you probably encountered "free monads". Monads themselves are scary enough, but free monads!? Luckily as usual things are much simpler then they might sound.

As the title suggests, we know that the answer to our problems is a Free Monad. But what is the question?

(Not to repeat the many great monad tutorials, the text below assumes that you are roughly familiar with the concept of a monad, the fact that each monad has a pure: A => M[A] and flatMap: M[A] => (A => M[B]) => M[B] methods and that monads can be used to describe how to compute a value in a context using a sequence of steps. All examples are in Scala.)

The problem

Most programs calculate some kind of values. For example, given an HTTP request we want to calculate a response, that can be a String, a number or other data type. The calculation process usually involves interacting with the external environment: reading from a database, querying a microservice (how else!) for data etc.

Separating concerns is generally established to be a good idea in computer science, so here as well, we'd like to somehow separate the external, side-effecting interaction from our beautiful, pure business logic. This can be done in a couple of ways (we'll also discuss this a bit later), but for now let's take the following approach.

We will describe the external interactions as data using a family of case classes. Each external interaction results in data of some type (specified as a type parameter). This might be a very simple 1-class family, or a rich language corresponding to our domain. For example, if the only thing we can do is invoking a single external service:

// common type for all external interactions yielding data of type A

sealed trait External[A]

case class InvokeTicketingService(count: Int) extends External[Tickets]You can view these classes a base instruction set of a domain-specific language.

Firstly, having this basic instruction set, we'd like to construct programs using them as primitives. Or rather, we want to construct descriptions of programs, and execute them later. Notice that we haven't yet provided any kind of interpretation to what these instructions (e.g. "invoking a service") actually mean. Formally, we want to define a data structure Program[External, A] (parametrised by the type of the base instructions and the result of the whole program).

Secondly, having a description of a program, and an interpretation for our base instruction set, we'd like to extend this interpretation to cover the programs we have built. More specifically, given a function interpretBase[A]: External[A] => M[A], where M is any monad, we'd like to extend this to a function interpretProgram[A]: Program[External, A] => M[A]. It would be nice if there was only one way to create such a (well-behaving) extension so that we don't have to make any additional choices.

As you've probably guessed Program[External, A] = Free[External, A], that is it's the free monad over External.

But let's not jump ahead. Now that we have our requirements, lets first see what "free" means.

Free structures

"Free" is a term used in several related branches of mathematics, for example in universal algebra or category theory. What does it mean?

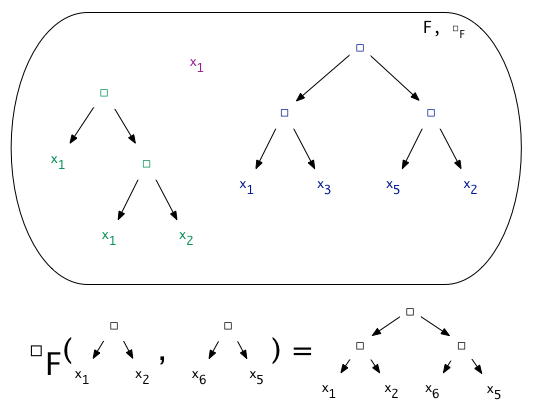

Let's constrain our world to any kinds of sets which have a binary operation defined, □: A => A => A. This operation can be interpreted in a number of ways: as multiplication in the set of integers (where □ becomes *), as subtraction in the set or real numbers, or as concatenation in the set of strings. We will use □_A to distinguish a specific interpretation from the general symbol □.

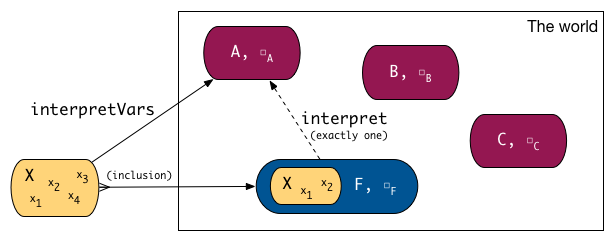

In the world of sets with a □ operation, a free structure over a set of variables X will be a specific set F with a specific □_F operation (in our world, only sets with □ exist), such that for any other (A, □_A), any function interpretVars: X -> A will extend uniquely to a well-behaved function interpret: F -> A.

What does well-behaved mean? Only what you would expect:

- interpreting the result of

□_Fon some arguments is the same as interpreting the arguments and then applying□_A(formally:interpret(f_1 □_F f_2) = interpret(f_1) □_A interpret(f_2)). - as

interpretis an extension ofinterpretVars, for all variables fromX,interpret(x) = interpretVars(x)

What is F then? Abstract syntax trees! That is, all finite trees constructed with the help of □ and the variables from X. Note that such a set belongs to our world: the interpretation of □ in F takes two trees as arguments, and creates a bigger tree. For any other A, □_A extending a interpretVars: X -> A to interpret: F -> A is quite straightforward, for any element in F you just take the AST and evaluate it using □_A. It's also quite easy to show that there's only one such well-behaved extension.

In other words, if we know what are the values of the variables (each variable is assigned a value from A), we can calculate the value of any expression.

But still - why that specific word, "free"? I don't know what was the original motivation, but as I understand it, F is free from any specific interpretation, or free to be interpreted in any way. That is, it doesn't impose any constraints on what □ could mean. Each combination of the variables and □ can, but doesn't have to, yield a different value.

It is also a minimal such construction, that is it doesn't contain anything extra (no extra elements). That minimality is needed to ensure that the extension function for a given interpretVars is unique (if there was anything extra, we could interpret it in any way).

Free monad

Now that we know what "free" means, we can apply that to monads! Instead of □, we have pure and flatMap, and instead of variables, we have a basic instruction set S[_] (in our specific example, External[_], but we'll use S[_] to make thing shorter).

Hence, our programs will be abstract syntax trees expressed as nested case class instances! The base trait here is Free[S[_], A], which is a program returning a value of type A with basic instructions of type S[_]:

trait Free[S[_], A]

case class Pure[S[_], A](value: A) extends Free[S, A]

case class FlatMap[S[_], A, B](p: Free[S, A], f: A => Free[S, B]) extends Free[S, B]

case class Suspend[S[_], A](s: S[A]) extends Free[S, A]We have three types of nodes, two for the basic monad operations, and one which is a wrapper for a base S[_] instruction.

We can quite easily lift any instruction to a free monad value (by wrapping with Suspend) as well as implement pure and flatMap methods which simply create the wrappers. Using these we can define a monad instance for Free, and get all the monad benefits, e.g. use the nice for comprehension syntax to compose our programs.

We have solved the problem of creating descriptions of our programs with the basic instructions S[_], we still need to run them to have any job done at all.

Given an interpretBase[A]: S[A] => M[A] function, we can quite easily extend that to run on our programs. We interpret all FlatMap nodes using M.flatMap (the flat map from the monad in which we run the interpretation), similarly for pure. And for Suspend nodes, we fall back to the original function. Hence we get an interpret[A]: Free[S, A] => M[A] function. It is quite easy to show to there's only one way in which we can create the extension so that it is "well-behaved".

And that's all there is to it! I hope free monads don't sound as scary as they did before.

Check: Free and tagless compared - how not to commit to a monad too early

What do we get

We have a way of constructing programs over an arbitrary base instruction set, but what did we gain?

First, we have entirely separated the description of our program from the interpretation of the side-effects. This can be very useful in testing, where instead of the multi-threaded AsyncNetwork monad we can use one which just returns constant values, but even if you only ever use a single interpreter, I would argue that having such a separation of concerns is a good thing to have.

Secondly, our programs are now ordinary values, and we can manipulate them as such freely. These values are usually pure and immutable, that is we can re-use them in many contexts and create new ones without worrying that some side-effect might happen. Things will only get executed once we run the interpretation.

Thirdly, we know exactly what kinds of side-effects may happen. If we use the AsyncNetwork monad, it is quite natural to expect that some network I/O will take place over multiple threads. If we use the Id monad it is natural to expect that no external resources will be involved (no guarantees, though, you can always do a System.exit somewhere in the code).

How did I live without free monads until now?

That's what you are probably thinking right now - how did I ever manage to write a program without a free monad?

It is of course also possible to separate construction from interpretation in other ways (or not to separate at all, but I'll assume for now that we do want the separation). Following our example, in a "traditional" OO-system you might have a service:

trait TicketingService {

def invoke(count: Int): Tickets

}this looks very similar to the case class InvokeTicketingService(count: Int) extends External[Tickets] we had before, with the main difference being that we now have a method instead of a class. However, note that the method signature constrains us in how the method can be implemented: it needs to be synchronous, as we return a strict Tickets value, not e.g. a Future[Tickets].

Creating a service which returns a future instead:

trait TicketingService {

def invoke(count: Int): Future[Tickets]

}doesn't really solve the problem. The details on what kind of side effects we allow and how they are interpreted already leaked into the service interface (we only allow futures). Well then we just need another level of indirection!

trait TicketingService[M[_]] {

implicit def m: Monad[M]

def invoke(count: Int): M[Tickets]

}Now by creating various service implementations and injecting wherever needed we can control the side effects. But then comes the next challenge. We have some code which can invoke the ticketing service multiple times, and we want surround them with some kind of transaction. Implementing that is quite straightforward when we can manipulate the program as a value; the interpreter can just start&stop the transaction at the right time. No need to propagate a transaction context or things like that. That's exactly what DBIOAction.transactional in Slick 3 is doing.

How would then a more complete example look like using a free monad? We'll just use the Free definition from above:

sealed trait External[A]

case class InvokeTicketingService(count: Int) extends External[Tickets]

def purchaseTickets(input: UserTicketsRequest): Free[External, Option[Tickets]] = {

if (input.ticketCount > 0) {

// creates a "Suspend" node

Free.liftF(InvokeTicketingService(input.ticketCount)).map(Some(_))

} else {

Free.pure(None)

}

}

def bonusTickets(purchased: Option[Tickets]): Free[External, Option[Tickets]] = {

if (purchased.exists(_.count > 10)) {

Free.liftF(InvokeTicketingService(1)).map(Some(_))

} else {

Free.pure(None)

}

}

def formatResponse(purchased: Option[Tickets], bonus: Option[Tickets]): String = ...

val logic: Free[External, String] = for {

purchased <- purchaseTickets(input)

bonus <- bonusTickets(purchased)

} yield formatResponse(purchased, bonus)The logic value is just a description of a program - nothing has been executed yet. We can now run it by providing an interpretation of External e.g. to Future:

val externalToServiceInvoker = new (External ~> Future) {

override def apply[A](e: External[A]): Future[A] = e match {

case InvokeTicketingService(c) => serviceInvoker.run(s"/tkts?count=$c")

}

}

val result: Future[String] = logic.foldMap(externalToServiceInvoker)

// show the result to the userOr in tests, we can provide an alternative interpretation:

val testingInterpeter = new (External ~> Id) {

override def apply[A](e: External[A]): Id[A] = e match {

case InvokeTicketingService(c) => Tickets(10)

}

}

val result: String = logic.foldMap(testingInterpeter)

// assert that the result is correctCheck out this Gist if you'd like to see full working implementation.

To sum up - it is possible to live without free monads, and there's definitely a lot of very good code which proves that, but sometimes using free monads you can create elegant, composable, cleanly separated (responsibility-wise) programs. Yet another tool in our programming toolbox!

Further reading

There's also quite a lot of existing material on free monads! I think the best resource on functional programming in Scala is, well, the Functional Programming in Scala book.

There are at least two implementations of free monads in popular Scala libraries, one in Scalaz and one in Cats. The one in Cats is shorter, simpler (and probably doesn't have as many features) but then also easier to understand.

There's so many free monad in Haskell tutorials that I won't even try to single out any of them. As for Scala, you can take a look at Free monads in Scalaz and Free Monads Are Simple.

By the way - the above easily translates to applicatives. So you already know what free applicatives are, for free!