Windowing data in Big Data Streams - Spark, Flink, Kafka, Akka

Processing data in a streaming fashion becomes more and more popular over the more "traditional" way of batch-processing big data sets available as a whole. The focus shifted in the industry: it’s no longer that important how big is your data, it’s much more important how fast you can analyse it and gain insights.

Many companies discovered that they don’t really have "big data" (the exact meaning of which was never defined precisely); but they might have several data streams coming their way, just waiting to be leveraged. That’s why some people are now talking about fast data instead of the now old-school big data.

With streaming, time becomes one of the main aspects. That’s why it needs first-class handling. And it also brings some first-class problems, which we’ll discuss in this post.

Borrowing the definition of streaming from Tyler Akidau:

[streaming is] a type of data processing engine that is designed with infinite data sets in mind

we can never really hope to get a "global" view of a data stream. Hence, to get any value from the data, we must somehow partition it. Usually, we take a "current" fragment of the stream and analyse it.

What’s current? It might be the last 5 minutes, or the last 2 hours. Or maybe the last 256 events? That’s of course use-case-dependent. But this "fragment" is what’s called a window. There’s a number of ways in which we can window data, and later process the windowing results.

A great introduction to processing data streams, which also introduces the many windowing concepts in depth is presented in Streaming 101 and Streaming 102 by the already mentioned Tyler Akidau. It wouldn’t make sense to repeat it here, so I’ll just present brief definitions of the terms we’ll be using later, to classify various data windowing aspects:

How to classify data windows

What’s the time?

During processing, each data element in the stream needs to be associated with a timestamp. When we say "events in the last 5 minutes" - which 5 minutes do we mean? This can be done in three ways:

- event-time - a logical, data-dependent timestamp, embedded in the event (data element) itself

- ingestion-time - a timestamp assigned to the event when it enters the system

- processing-time - the wall-clock time when the event is processed

Event-time, while most useful, is also the most troubling: it gives the least guarantees; events may arrive out of order or late, so we can never be sure if we saw all events in a given time window. Processing-time is easiest, as it is monotonic: you know precisely when a 5-minute window ended (by looking at the clock), but also much less useful.

Types of windows

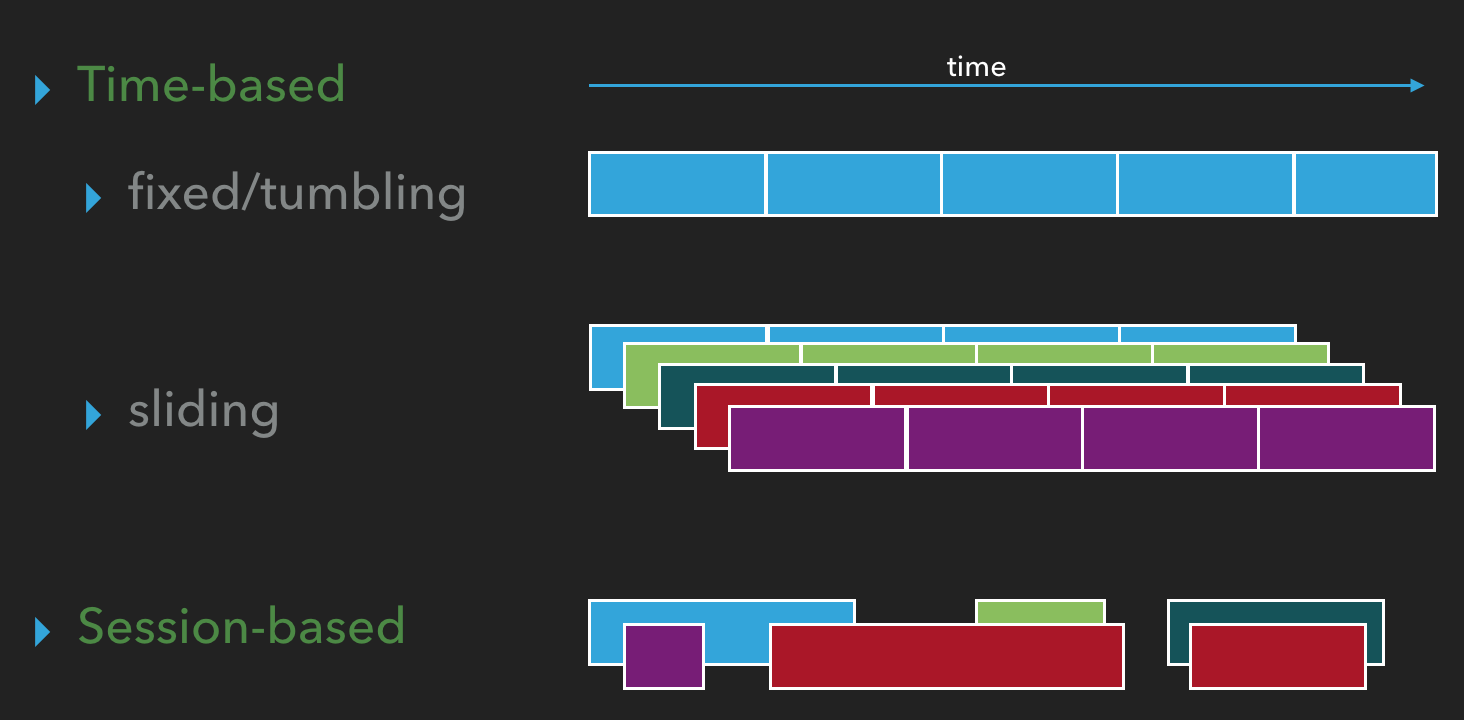

Windows can be:

- fixed/tumbling: time is partitioned into same-length, non-overlapping chunks. Each event belongs to exactly one window

- sliding: windows have fixed length, but are separated by a time interval (step) which can be smaller than the window length. Typically the window interval is a multiplicity of the step. Each event belongs to a number of windows (

[window interval]/[window step]). - session: windows have various sizes and are defined basing on data, which should carry some session identifiers

Out-of-order handling

As we hinted when discussing event-time, events can arrive out of order. For example in IoT, when you are receiving a stream of sensor readings, devices might be offline, and send catch-up data after some time. That’s why we definitely have to allow for some lateness in event arrival, but how much? We can’t keep all windows around forever, as this would eat all available memory. At some point, a window has to be considered "done" and garbage collected.

This is handled by a mechanism called watermarks. A watermark specifies that we assume that all events before X have been observed. This is of course a heuristic, as we usually can’t know that for sure. The heuristic has to be picked so that it strikes a good balance between including as much late data as possible and not delaying final window processing too much.

Any events older than the current watermark are dropped. An example of a heuristic is a watermark that is always 5 minutes behind the newest event time seen in an event; that is, we allow data to be up to 5 minutes late.

Manipulating the data

Once we accumulate data (events) in a window, to get value, it needs to be somehow manipulated. There’s a number of options:

- basic operations such as

map,filter,flatMap, ... - aggregate:

count,max,min,sum, etc. - fold/reduce using an arbitrary function

This allows us to get a window result value for each window.

Triggers

Having a way to obtain a value from a window, we still need to decide when to run the computation. In other ways, we need to specify what triggers it. Some of the possibilties (can be combined):

- watermark progress: compute the final window result once the watermark passes the window boundary

- event time progress: compute window results multiple times, with a specified interval, as the watermark progresses

- processing time progress: compute window results (multiple times) basing on a given interval measured against wall-clock time

- punctuations: data-dependent

Accumulation of results

Window results can be computed multiple times. How to handle the new values?

- discard old value, use only the new window result

- accumulate new value with the old value (e.g. add results to a counter)

- retract & accumulate: specify the old value to retract, replace with new value

Which strategy is best depends on where the results end up: is it a SQL/NoSQL database, a monitoring system, a graph, report?

Windowing in practice

Let’s now compare a couple of popular systems and see how they classify when it comes to windowing data taking into account the above mentioned aspects.

We’ll take a look at Spark, Flink, Kafka Streams and Akka Streams. It’s by no means a comprehensive list - there are many more streaming systems out there, but these seem to be quite popular.

Spark Streaming

Spark Streaming is one of the most popular options out there, present on the market for quite a long time, allowing to process a stream of data on a Spark cluster. It builds on the usual Spark execution engine, where the main abstraction is the RDD: Resilient Distributed Dataset (you can think about it as a replicated, parallelised collection). In Spark Streaming, the main abstraction is a DStream: a discreticised stream. A DStream is defined by an interval (e.g. 1 second), which is used to pre-group the incoming stream elements into discrete chunks. Each chunk forms an RDD and is processed by the "normal" Spark execution engine. Hence this is not "true" streaming, but micro-batching. However, you can implement quite a lot of streaming operations on top of such an architecture.

What about windowing options? The DStream.window() API has the following capabilities:

- tumbling/sliding windows

- only processing-time; no event-time support

- no watermarks support (which wouldn’t make sense with processing-time anyway)

- triggers at the end of the window only

This is quite limited - can be useful, but still doesn’t look like much with all the options we’ve discussed. That’s why we now have ...

Spark Structured Streaming

Structured Streaming is available as an alpha-quality component in Spark 2.0, and is the next-generation of streaming in Spark. As a programmer, you don’t see the micro-batch anymore, instead the API exposes a view of the data as a true stream. You can group the stream on any columns, and additionally you can also group by a window (groupBy(window(…))). That’s where all the windowing possibilities start:

- structured streaming has event-time support (in addition to processing-time of course) by specifying an arbitrary column in the dataset as the one holding event time

- watermarks are not supported yet - they are planned for 2.1. This can cause significant problems currently: the window data is never removed, causing memory usage to grow indefinitely

- tumbling/sliding windows support. Session windows are planned for 2.1

- triggers: processing time only. In specified (processing-time) intervals, windows changed since the last trigger are emitted.

Flink

Apache Flink reifies a lot of the concepts described in the introduction as user-implementable classes/interfaces. Like Spark, Flink processes the stream on its own cluster. Note that most of these operations are available only on keyed streams (streams grouped by a key), which allows them to be run in parallel. The interfaces involved are:

TimeCharacteristic: enumeration of.Event,.Ingestion,.ProcessingTimestampAssigner: assigns timestamps to events (when using event-time), but also generates watermarks. There are some built-in options, like generating a watermark in specified event-time intervals, but custom implementations can be providedWindowAssigner: for each data element, assign windows corresponding to it. Built-in options: tumbling/sliding/global windows. A custom implementation can be used to implement session windows.Trigger: event/processing time (when watermark is passed), continuous event/processing time (based on an interval), element count

Thanks to that elasticity, all of the concepts described in the introduction can be implemented using Flink.

Kafka

Apache Kafka, being a distributed streaming platform with a messaging system at its core, contains a client-side component for manipulating data streams. The data sources and sinks are Kafka topics. Like in previous cases, Kafka Streams also allows to run stream processing computations in parallel on a cluster, however that cluster has to be managed externally. Like with any other Kafka stream consumer, multiple instances of a stream processing pipeline can be started and they divide the work.

As for windowing, Kafka has the following options:

TimestampExtractorallows to use event, ingestion or processing time for any event- windows can be tumbling or sliding

- There are no built-in watermarks, but window data will be retained for 1 day (by default)

- trigger: after every element. The results are stored in an ever-updating

KTable. AKTableis table represented as a stream of row updates; in other ways, a changelog stream. The each-element triggering can be a problem if the window function is expensive to compute and doesn’t have a straightforward "accumulative" nature.

The options here are much more modest comparing to Flink, but the processing and clustering models are simple to understand, which is definitely a plus when designing a system. And - it works great with Kafka! ;)

Update: Under KIP-63, window output will be cached hence triggering not on each element, but only when the cache is full. This should improve preformance of window processing.

Akka

Akka Streams is a bit different than the other systems described here - it is designed for processing data on a single node, there’s no clustering support. Still, very large amounts of data can be processed on a single node when streaming - and sometimes that’s more than enough. There’s no support in Akka Streams for windowing data built-in, but it’s quite easy to do as described in another of our blogs. As it’s a "manual" implementation of windowing in some aspects it’s quite flexible:

- event/ingestion/processing time: no real difference, as the "time" concept only exists on the custom implementation level

- windows: sliding/tumbling/session, custom code to assign windows to each element (as in Flink)

- watermarks: can be implemented

- trigger: only window-close

The biggest limitation lies in the triggers, but probably can be also overcome using a custom graph processing stage.

Summing up

As you have seen, the presented systems vary widely in how data can be windowed. Some offer only the basics, like Spark Streaming, some have a very wide range of windowing features, such as Flink.

However, keep in mind that windowing in only one of the aspects of a stream processing engine. Another important way in which the engines differ is how local state can be maintained, and how it is persisted and recovered in case of a node crash. Also, there are differences in the processing guarantees (at-least-once vs exactly-once vs at-most-once) given by the systems.

And then there’s also Apache Storm, Amazon Kinesis, Google Dataflow, Apache Beam, and probably many other stream processing systems out there, not covered in this comparison.

Ultimately, whether to choose Spark, Flink, Kafka, Akka or yet something else, boils down to the usual: it depends.